I Got the Idea I Wasn't Real

Reading Naomi Klein's "Doppelganger"

I Got the Idea I Wasn't Real: Reading Naomi Klein’s Doppelganger

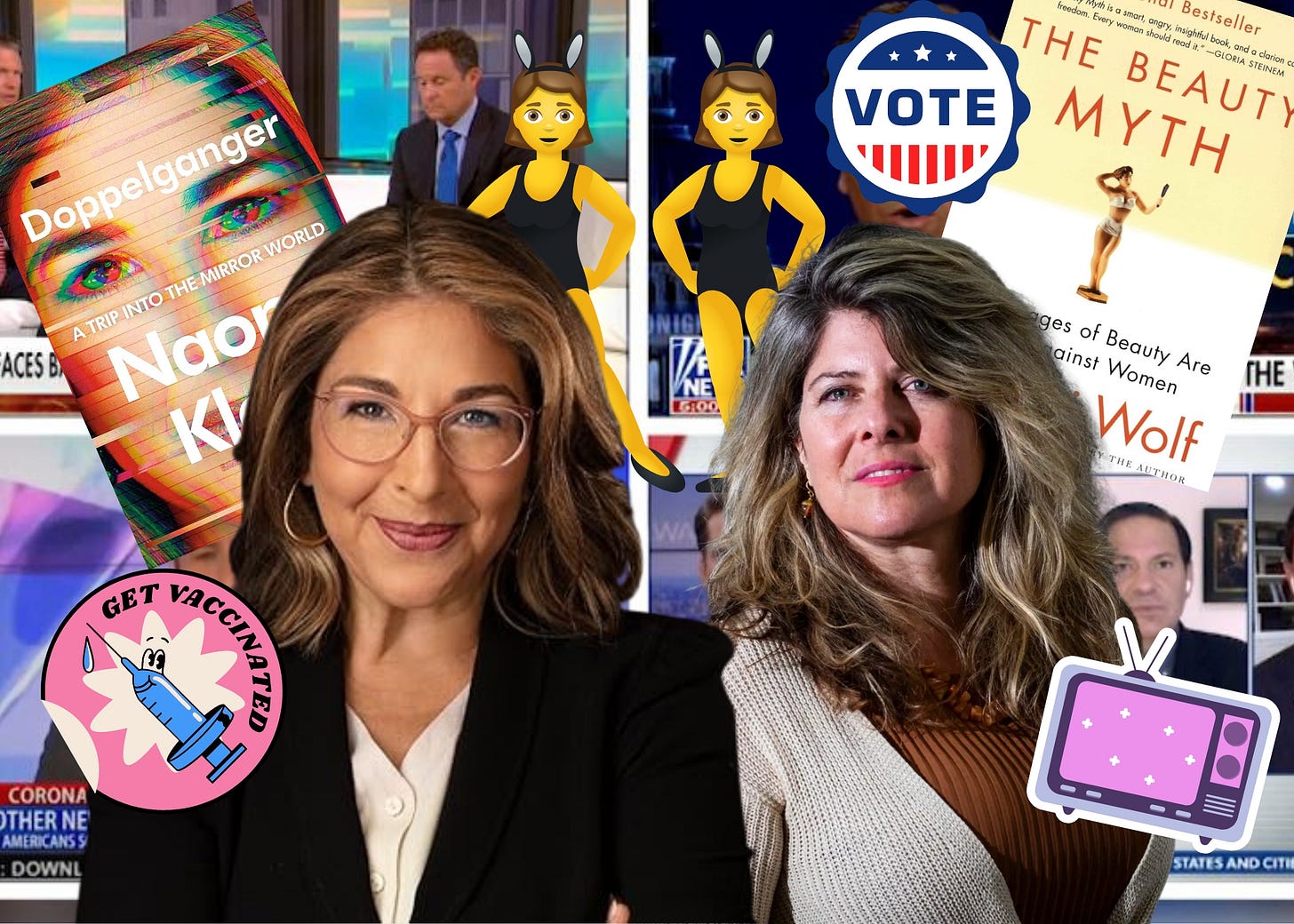

In Naomi Klein’s memoir/treatise/exhortation Doppelganger—which begins as an examination of her relationship to her professional doppelganger and certified nut Naomi Wolf, then becomes so much more—she writes of feeling as if she were disappearing during the early days of the pandemic. I, too, felt like I began to slowly disappear in 2020, and have only become more transparent since, fading like Michael J. Fox’s hand as he invents rock and roll in Back to the Future. So this resonated with me. Between leaving my religion and the friendships and family members that came with it, and losing tactile contact with the outside world, it sometimes felt like I had simply ceased to exist, so meager was my impact on the world around me.

I’m still struggling with this. As a freelancer, I have no colleagues, just clients. My social network has shrunk considerably. And a long stretch of unemployment meant I couldn’t justify leaving the house just for the hell of it, which, in NYC, famously costs at least $100 a day. It was like I didn’t exist outside of my own four walls.

Like Klein, I also coped by spending too much time online, a habit I have yet to break. And as I was reading Doppelganger, I was heading down the rabbit hole of my own professional doppelganger—by which I mean: I was scouring LinkedIn for the profile of the person who got a job I interviewed for over the summer and really, really wanted. I didn’t like what I found. She graduated college in 2015. She’s been freelance almost her entire career. She has none of the big brand experience I have. She has none of the travel industry-specific experience I have, which was relevant to the job. SO WHY DID THEY PICK HER??

The interview process involved a personality test, so I know junk science played at least some role in the decision. And my HR contact kept asking me if I was ok with the salary they were offering and suggesting we could negotiate a bonus structure to make up for the gap she expected to find between their range and my expectations, which were at an all-time low since unemployment had just run out. It was honestly refreshing to have someone worry they can’t pay me enough, when I had made less than what they were offering at those big brand jobs where they were happy to pay me as little as possible despite the company’s near limitless funds.

I’m glad, I seethed while hunched over my laptop, that all my years of experience at jobs that underpaid me but looked good at my resume, or that emotionally abused me but gave me experience relevant to the jobs I actually wanted, or that underpaid me but kept me employed during economic upheaval, or that paid me ok but made sure I knew they didn’t think I was worth it, or that gave me a raise as part of their “salary transparency initiative” and then laid me off the next month, have qualified me to lose out on jobs to people younger and less experienced. I’m glad my entire career has qualified me for homelessness.

When I finally forced myself to close the tab, I opened up my email and sent a reminder to a freelance client, all but begging them to pay an invoice in time for me to make rent.

This woman, whose name I’ve already forgotten and is probably plenty smart and capable, isn’t my first professional doppelganger. Back in 2011 the job market was still recovering from the housing crash and I had just finally landed a marketing coordinator job for $25k a full two years after graduating college, which took me eight years instead of four because I had to pay my way through as I went. I took the role over from another 2009 grad from my school, but one who had completed her degree on the usual timeline and landed a full-time marketing position well before I did. She was leaving the job because she was dating another employee in the small office and it was making everyone uncomfortable. Plus, I would later learn from our mutual boss, she wasn’t very good at her job anyway. Let’s call my doppelganger “Jessica.”

This organization hosted a lot of events, and for the first few months attendees would approach me saying something like, “So you’re the new Jessica!” or “I miss Jessica!” or “Jessica was the best, you’ve got big shoes to fill!” Jessica had made a lateral move to a marketing coordinator position at a local real estate agency where I had also worked one summer as a receptionist. She often attended these events in her new role, so I got to know the woman I was being compared to. Jessica was friendly and outgoing and talkative and…how many ways are there to say that someone’s primary skill is extraversion?

Extraversion has never been my skill, but I was pretty good at this job. I was promoted to marketing manager three months in, I launched a networking group for young professionals that Jessica had never been able to get off the ground. I even took over leadership of a community clean up event, although I can’t really brag about that one because the other organizers complained to my boss about me not being involved enough (maybe because I was doing three jobs in one for near poverty wages AND had to work side hustles to comfortably afford groceries???).

If I were more chatty and outgoing, though, I probably could have gotten away with doing less. That’s what I learned from Jessica. Once in a while I would mention to my boss that people were still bringing her up to me and my boss would say something like, “Listen, she’s very nice, but she was not good at her job, so don’t let that get to you.” But I was also pretty sure she had been paid more than me, since she started our job before a major restructuring that slashed salaries.

When I finally quit our job, I went to a digital marketing agency where I got more promotions and raises, and then to New York where I got…technically more money at jobs I was overqualified for and got to live in the city. Jessica became a real estate agent, having failed to ever progress past “marketing coordinator.” And that’s fine. I’m sure she’s a homeowner by now, and she’s certainly still better liked than me. And she ended up marrying the guy she met at our job. Most people would say she came out on top here.

But now every time I’m passed over for an opportunity in favor of someone with less experience and fewer qualifications, I can’t help but hear some middling midwestern accounting manager saying “So you’re the new Jessica! You’ve got big shoes to fill!” as they reach their hand out to greet me in some brightly-lit hotel ballroom.

Jessica wasn’t my only doppelganger. There was the other Rebecca Woodward at IBM, who complained to me that my teammates were constantly emailing her by accident, but refused to do anything about it like, say, replying to tell them they were emailing the wrong Rebecca. I hated that job and my boss hated me and not receiving any of the emails intended for me certainly didn’t help the situation.

Then there was Eliot Spitzer’s call girl sex worker Rebecca Woodward, who really fucked up my Google alerts for a while. And I’m still locked in a one-sided battle with Bob Woodward’s niece Rebecca, who was first to claim our name at the local wine shop and keeps getting all my loyalty points.

Each little battle I wage with another Rebecca Woodward or another professional who’s getting the jobs I want while I keep having to take what I can get, makes my qualifications feel less real, makes me feel less real, like a ghost realizing they’re dead because their hands simply pass through the material objects they try to move.

This fall I applied for a contract gig doing content marketing for a client in healthcare. When I applied, I made sure to call out that I had once won a prestigious award for a content marketing campaign I worked on for a healthcare client. An hour later I received an email from the recruiter telling me I “didn’t have the experience they were looking for” and, losing my cool, I responded, “How can that be when I have literally won an award for doing this exact kind of work?” I got no response. It felt like I wasn’t real.

In Doppelganger, Klein is in a constant battle with Wolf over her professional reputation—which is at risk anytime someone confuses their names online—and the very nature of truth itself. Her book is a dissection of doubles, and truth/truthiness is one of them. Klein claims that our doppelgangers are the inverse of us. The extraverts to our introverts, the inexperienced newcomers to our seasoned experts, the people who are loud and bad at their jobs to our people who are quiet and at least pretty good at their jobs. And doppelgangers exploit the distance between the two to attract attention. If she’s so good at her job, why is she willing to take the salary we’re offering?

I don’t often find myself comparing my life to that of an Instagram influencer or a celebrity, but I do still get sucked into the vortex of comparing myself to rivals at work, where accomplishments you can list on paper and examples of successful work you can include in your portfolio are supposed to matter, but rarely do. Maybe I would go less insane if I accepted that we’re living, or at least working, in what Klein calls the “mirror world” and here the Jessicas will always win.

Recommendations:

Maris Kreizman on the hellscape that is Goodreads, and virtually every other digital property intended for readers.

Kady Ruth Ashcraft asking the burning question: Do famous men know how to read?And, if they do, why don’t they start book clubs? (Chris Pine’s book club, when?!)

Casey Newton on how platforms killed Pitchfork and, by extension, music criticism as a serious discipline.

The hosts of The New Yorker’s Critics at Large podcast on the case for criticism and the role of the critic, especially Vinson Cunningham’s definition of the critic as someone who loves experiences and wants to stave off death by extending them through critique.

What Went Wrong, a podcast about everything that goes wrong in a movie production, making you wonder how any good movies make it to our screen.